The rules for rewriting the Pinochet-era Constitution set new standards in creating space for women, Indigenous peoples, and people with disabilities.

Over May 15 and May 16, Chileans will elect the 155 delegates charged with writing the country’s new constitution. The constitutional process is already 19 months old, launched by the October 2019 protests in which hundreds of thousands of Chileans denounced an unresponsive and insular political class. The legitimacy of the constitutional convention now depends on the distance delegates can set between themselves and the Chilean politicians of the past.

The good news for those seeking political renewal is that Chile is poised to elect the world’s most diverse constitutional convention. There will be gender parity, since half of the candidates and half of the elected delegates must be women. There are seats reserved for Indigenous peoples. At least 5 percent of parties’ candidates are people with disabilities.

These measures reflect international norms emphasizing the importance of diverse legislatures. In adopting them, Chile’s political elites acknowledged that voters’ acceptance of any new charter hinges on the diversity those writing it. By including women, Indigenous peoples, and people with disabilities, Chile raised the global standard for representative democracy, but these victories did not happen without a fight.

An Awakening in Chile

Constitutional conventions are rare for countries not emerging from civil war or dismantling authoritarian governments. Chile looks like an outlier globally—but less so in South America, where countries like Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador wrote new constitutions years after democratization began, when leftist parties with new visions came to power.

Chile has held free and fair elections since 1989, but outgoing dictator Augusto Pinochet left behind a constitution that stymied reform. In Chile as elsewhere in the region, discontent simmered as the democratic transition remained unfinished. Chile has held free and fair elections since 1989, but outgoing dictator Augusto Pinochet left behind a constitution that stymied reform. Even change-oriented presidents like Michelle Bachelet proceeded cautiously, chipping away at institutional inertia and socioeconomic inequality without upending the status quo completely.

The October 2019 protests did not launch an armed insurgency, but they did paralyze the country. Protest movements in the preceding decades—like the 2016 marches against the Pinochet-era individualized retirement accounts—previewed citizens’ longstanding frustrations. The final straw came when the right-wing government of Sebastián Piñera hiked transit fees. Popular anger flared in what’s now called the estallido (awakening). From the capital Santiago to the small cities of Patagonia, people took to the streets over economic, social, and political inequality.

The estallido revealed that democracy cannot sustain itself on procedural grounds alone. Large proportions of the population demanded substantive changes: less inequality and more justice. Piñera did meet some of the protesters’ demands, like raising taxes on the wealthy and increasing the minimum wage. But these efforts were once again too little and too late. Protesters faced police brutality, but they returned to the streets week after week, forcing elites to reckon with their demands for deeper change.

Crafting Inclusionary Rules

The Pinochet Constitution, like many of the world’s founding charters, was written by a closed group of mostly men, all economic and political elites. Those demanding big change wanted a constitution more reflective of Chilean society, but it took months to get Congress on board.

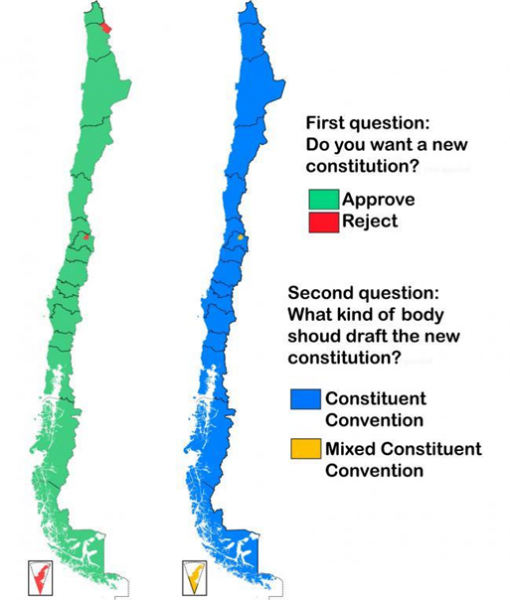

Legislators began planning the constitutional process in November 2019, as the protests continued. They organized a two-question referendum. First, voters would vote “yes” or “no” on whether Chile should write a new constitution. Then, no matter their answer, voters would choose the body’s composition: should the assembly be composed exclusively of citizens elected as delegates, or should half the members be citizen-delegates and the other half current legislators?

Results of the first and second question of the 2020 plebiscite. (NACLA / B1mbo / Wikimedia)

Elections for the citizen-delegates were set to follow the system used for electing the lower house. Adopted in 2015, the election system includes a 40 percent quota for women congressional candidates, but in the 2017 elections, women actually won only 23 percent of seats. Julieta Suárez Cao, political science professor at Chile’s Universidad Católica, recalls her reaction to using the congressional election system for the constitutional assembly. “In this context,” she explains, “we needed affirmative action to work.” A weak gender quota simply would not do.

Suárez Cao and colleagues mobilized the Red de Politólogas, a network of feminist political scientists, which collaborated with congresswomen to insist on a constitutional convention with gender parity. Following extensive lobbying, they won: women would comprise half the candidates and half the victors. To ensure the latter, Congress later settled on a “best loser” system. If women do not win half the district’s seats, the man (or men) who wins with the least votes will be bumped for the woman (or women) who loses with the most votes.

Chilean legislators could reach no consensus on mechanisms to include Indigenous peoples or people with disabilities, however. When the referendum arrived on October 25, 2020, gender parity was ensured, and activists had vowed to keep demanding guarantees for Indigenous peoples and people with disabilities. Choosing the all-citizens option clearly meant giving those outside the traditional economic and political elite a stronger voice in their country’s future—and this choice won in a landslide.

Yet debate over exactly how Indigenous peoples and people with disabilities would participate dragged on until December 2020. The lower house had approved a 10 percent candidate quota for people with disabilities in late 2019, but conservative senators countered with 1 percent. Conservative lawmakers also pushed down the number of reserved seats for Indigenous peoples from the mid-20s to the teens. A proposal to reserve a seat for an Afro-Chilean delegate was rejected.

Verónica Figueroa Huencho, professor at the Universidad de Chile and a Mapuche activist, reflected that space facilitating the political participation of Indigenous peoples “became threatening for those who have benefited from a democracy that does not actually represent Chile’s diversity.”

Finally, thanks to pressure from activists within the disability rights community and the Indigenous movement, Congress approved a 5 percent candidate quota for people with disabilities and set aside 17 seats for Indigenous candidates. Chile’s election agency later determined which Indigenous communities in which districts would receive seats, leaving 138 seats for the political party and independent candidates.

Inclusion with Resistance

The notion of citizen-delegates conjures images of a process open to everyday people, but that’s not quite the case. Most candidates are running in pacts formed by political parties, meaning parties could filter out certain candidates.

For instance, some outspoken supporters of gender parity paid a price. Pamela Figueroa Rubio, professor at the Universidad de Santiago de Chile and academic coordinator of the New Constitution Observatory, commented that parties “resisted choosing the most feminist candidates.”

Gender parity and reserved seats nonetheless promise women and Indigenous peoples some form of representation in the assembly, while candidates with disabilities have no guarantees. Javiera Viveros Alegría is among the 41 candidates with disabilities running for the convention. A librarian and poet, Viveros Alegría cited the quota’s insufficiency, commenting, “We should have reserved seats to guarantee our participation in writing the new constitution.”

The candidate quota has made people with disabilities visible, but whether visibility translates into influence remains to be seen.Indeed, Viveros Alegría and other candidates with disabilities face considerable challenges. They are often running against candidates with more name recognition and more resources. Accessibility barriers often limits their participation in virtual and in-person campaign events. The candidate quota has made people with disabilities visible, but whether visibility translates into influence remains to be seen.

New Global Standards

No matter who wins on May 16, Chile will achieve some milestones.

Chile will sit the world’s first constitutional convention with gender parity. Tunisia’s 2011 constitutional convention, held in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, used gender parity rules for candidates, but women candidates won only one-quarter of the assembly’s seats. Many countries, including 10 in Latin America, apply gender parity for congressional elections, but until now, no country has redistributed electoral spoils such that 50 percent women are guaranteed election.

The seats reserved for Indigenous peoples also go above-and-beyond other countries’ practices. The Venezuelan and Colombian congresses reserve seats for Indigenous peoples, but no more than two per chamber. By contrast, Indigenous peoples will comprise no less than 11 percent of Chile’s constitutional assembly.

So far, these inclusionary measures are only for electing the constitutional convention. Yet they faced such staunch resistance precisely because advocates would like to see them become permanent. An alliance of left-wing and independent politicians called New Treaty (Nuevo Trato) has called for a constitution with “absolute parity,” making gender parity mandatory for all decision-making bodies in the public and private sector. A collection of activists, politicians, and candidates has created the Indigenous Constitutional Platform, which argues that the new constitution must recognize Chile as multiethnic and must establish Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, autonomy, language, and culture.

Such constitutional articles have precedents. Two years ago, the Mexican Constitution added “parity in everything”—gender parity in all branches and levels of government. The recent constitutions in Bolivia and Ecuador included gender parity across the government and established the countries as multiethnic democracies.

“We have a slogan,” Viveros Alegría said, referring to people with disabilities. “Nothing about us without us, and for this new constitution to be representative and therefore legitimate, we ought to be included.” This saying echoes the hashtag used by women supporting gender parity: “Never again without us,” with emphasis on nosotras, the feminine version of “us.”

The lesson from Chile is clear. The more decision-making bodies look like those whom they purport to represent, the more legitimate they appear in the eyes of citizens—and perhaps the less prone to the protests over injustice and exclusion that rocked Chile in the first place.

May 12, 2021

– Jennifer M. Piscopo (@Jennpiscopo) is Associate Professor of Politics at Occidental College. Her research on gender and political representation has appeared in over 20 academic journals and in outlets such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, Ms. Magazine, and Americas Quarterly, among others.

https://nacla.org/news/2021/05/10/chile-constitutional-convention-election-women