New Global Witness report shows nearly 90% of all environment-linked killings were in the region, driven by land disputes, armed conflict and extractive industries.

Fermín Koop, 2023.

From: https://dialogochino.net/

At least 177 land and environmental defenders were killed last year for trying to protect the planet – one person every other day – according to a new report by the UK-based NGO Global Witness. The situation in Latin America remains particularly concerning, as 88% of the killings happened in the region, an ever-growing majority of the world’s cases.

The new figures bring the total number of defender killings up to 1,910 between 2012, the year the NGO started with its reporting, and 2022. However, the true number may actually be much higher, the authors said. Many cases go underreported as they happen in conflict zones or in places where there are restrictions and inadequate monitoring of the attacks.

“These are ordinary people trying to peacefully protect their homes, livelihoods and the health of the planet in general from harmful impacts of industries such as oil, gas, mining, agriculture and logging,” Gabriella Bianchini, an advisor and researcher at Global Witness based in Brazil, told Diálogo Chino. “They work to defend all of our lives.”

Colombia was found to be the deadliest country in the world, with 60 deaths in total last year – more than a third of all killings globally. These figures come despite the country’s move in October 2022 to ratify the Escazú Agreement, a legally binding regional treaty to protect environmental defenders, and is almost double the number of killings reported in the country in 2021.

At least 382 defenders have been killed in Colombia since 2012, making it the country with the highest number of reported killings globally during that time. Sirley Muñoz from the Somos Defensores NGO in Colombia told Diálogo Chino that this is directly related to territorial disputes and the strengthening of armed groups in the country.

“Colombia has a big debt with its environmental defenders,” Muñoz said. “Violence has marked our recent history, but the situation worsened in 2016 when the FARC [Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia] completed its demobilisation. Other illegal armed groups took over and the environmental defenders got caught in the middle of the crossfire. The report has to be a wake-up call.”

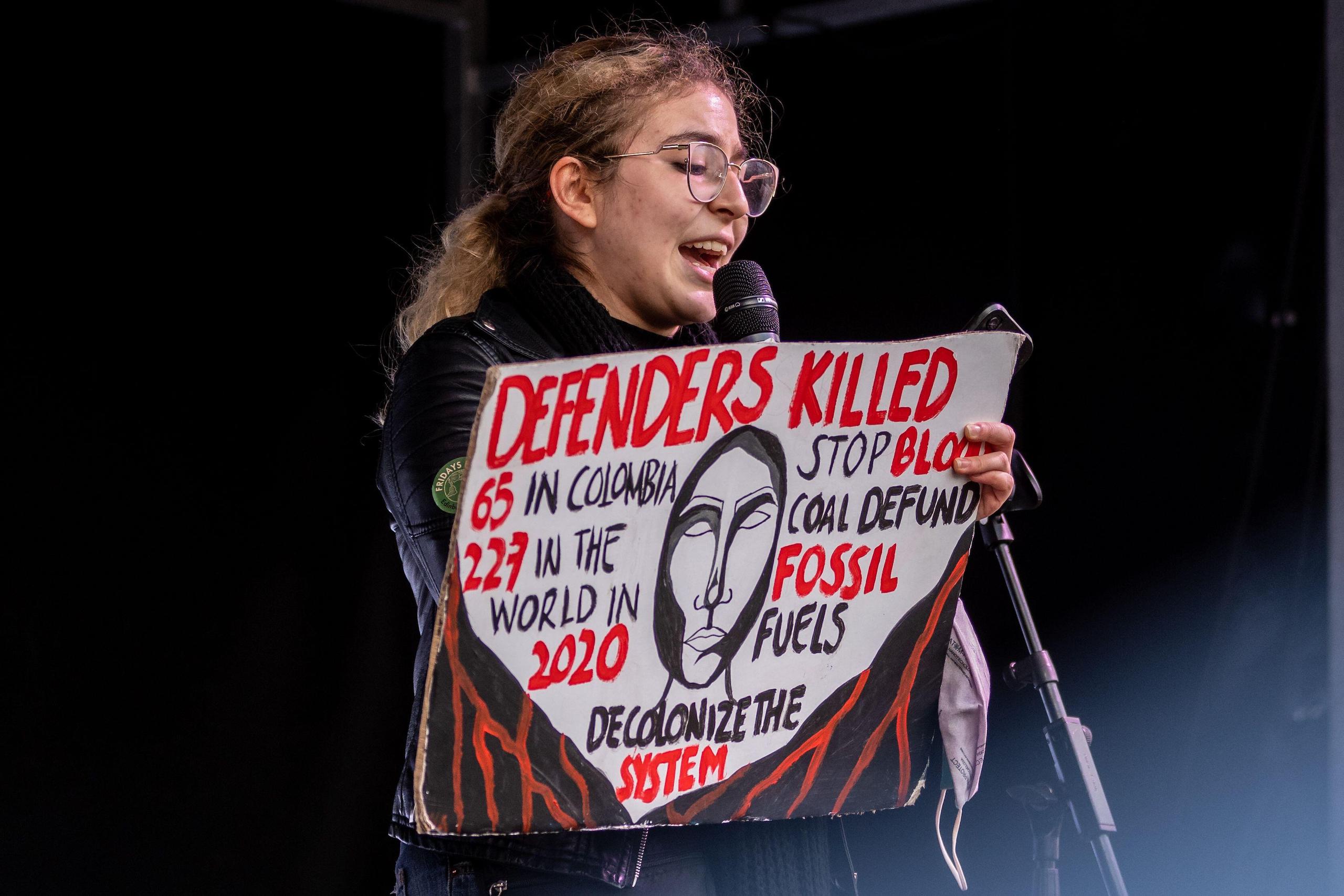

Colombian activist Sofia Gutierrez protests with a sign showing the number of defenders killed in Colombia and globally in 2020, during the Youth and Public Empowerment Day of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, in November 2021 (Image: Kay Roxby / Alamy)

Other vulnerable countries in the region where Brazil, where 34 defenders lost their lives, compared to 26 in 2021, and Mexico, although the 31 murders recorded in the country last year were a drop from 54 in 2021, when it was the country with the highest number of killings. With 14 land- and environmental-linked murders recorded, Honduras was the country with the world’s highest per-capita killings. Mexico has ratified the Escazú Agreement, while Brazil is yet to do so, having only signed the treaty at its creation in September 2018; Honduras has neither signed nor ratified the agreement.

Jorge Santos, coordinator of the Guatemalan human rights defence organisation UDEFEGUA, told Diálogo Chino there is a “severe setback” on human rights taking place in Central America. “It’s not only the private sector driving the violence against defenders. In many countries, we are seeing governments taking a more authoritarian stand,” he said.

A year of danger in the Amazon

For the first time, this year’s Global Witness report gave dedicated focus to the role of environmental defenders in the Amazon rainforest region, covering parts of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Suriname and Venezuela. In 2022, more than one in five of the 177 killings recorded globally (or 39 in total) happened in the Amazon, the researchers found.

“As guardians of the forest, land and environmental defenders are on the frontline of the Amazon’s devastating exploitation. They face dangerous companies acting with impunity, ruthless state security forces and contracted killers,” the report reads. “Defenders are systematically intimidated, criminalised, attacked and murdered.”

The most high-profile case last year was that of Brazilian Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips, who were killed while returning from a reporting trip in Brazil’s remote Javari Valley. Their murders shocked the world, and brought global attention to the threats faced by environmental defenders.

Around 1,000 kilometres from where the pair were found, in another area of the Brazilian Amazon, the activities of illegal gold miners have almost wiped out the Yanomani Indigenous community.

Maria Leusa Kaba, an Indigenous leader of the Munduruku community, speaks at an event on the Amazon in the city of Belém, Brazil in July 2023. She has received numerous death threats for her activism and opposition to illegal mining. (Image: Cícero Pedrosa Neto / Amazônia Real, CC BY NC SA)

Elsewhere, Maria Leusa Kaba of the Munduruku community in the Brazilian Amazon has received repeated death threats in recent years due to her opposition to illegal mining. “It’s a painful and sad reality,” she told Diálogo Chino. “They burned our houses to try to force us out of our lands. The Amazon doesn’t need any of the current extractive projects – it has to be protected.”

The situation is similar in Venezuela with the Uwottüja Indigenous community, who live in voluntary isolation along tributaries of the Orinoco River. In 2022, Virgilio Trujillo Arana, one of the community’s most prominent leaders, was killed by an unidentified hitman after vocally denouncing illegal mining and the accompanying violations in the Venezuelan Amazon.

In a video recorded before his murder, Virgilio said the community would continue to defend their land because without it they would disappear: “Whatever happens, happens. Without land, we disappear. That’s why we defend our territories.” Since 2014, 20 Venezuelan environmental defenders have been killed, 17 specifically in the Amazon.

Without land, we disappear. That’s why we defend our territories

Virgilio Trujillo Arana, assassinated leader of the Uwottüja Indigenous community

In Peru, Santiago Vega Chota, Yenes Ríos Bonsano and Herasmo García Grau, three environmental defenders from the Ucayali region, were killed in the last two years after defending their lands and forests. Peru is among the 10 most dangerous countries for environmental defenders, with 42 people killed since 2014 – half of them in the Amazon.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Amnesty International have called on the Peruvian government to comply with international rules and standards and protect defenders and their families. Last year, the country’s congress officially archived the bill through which the country would have ratified the Escazú Agreement.

The way forward

While the situation is dire, Global Witness highlighted some progress that occurred last year. The Escazú Agreement had its first conference of the parties (COP) in Chile, one year after coming into force, electing a group of public representatives to help with the treaty’s implementation. Also, the United Nations appointed the first ever Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders, with French human rights expert Michael Forst named to the position.

In Peru, the Supreme Court sentenced five illegal loggers to more than 28 years each in prison for the murder of four Ashéninka Indigenous leaders. However, the ruling was nullified this year. Meanwhile, in Mexico, a high court revoked the permits issued by federal authorities for the construction of the Veracruz port, questioned for its environmental impacts.

In its report, Global Witness calls on governments to create a safe environment for defenders and civil society to thrive, enforcing laws that protect defenders, and creating new ones. Relevant existing mechanisms such as the Escazú Agreement should be better used, the organisation said. In Latin America, 15 countries have so far ratified the treaty.

Governments should also report, investigate and seek accountability for reprisals against defenders, strengthening law enforcement and better monitoring the attacks, Global Witness said. Companies should also be required to carry out due diligence on human rights and environmental risks as this would make them more transparent to violence, it adds.

“More and more defenders are getting together and creating associations to protect themselves and the environment from threats and violations. We see this in different parts of the world,” Bianchini told Diálogo Chino. “The Escazú Agreement could be used as an example in other regions that do not have such instruments in place.”